Every breakthrough creates a maintenance burden. Every innovation demands upkeep. But our culture celebrates the new while ignoring what keeps the old running.

The most critical systems in our world are not the ones being built today. They are the systems built decades ago that continue functioning—not because of their original brilliance, but because of the quiet, uncelebrated work of maintenance professionals who understand them.

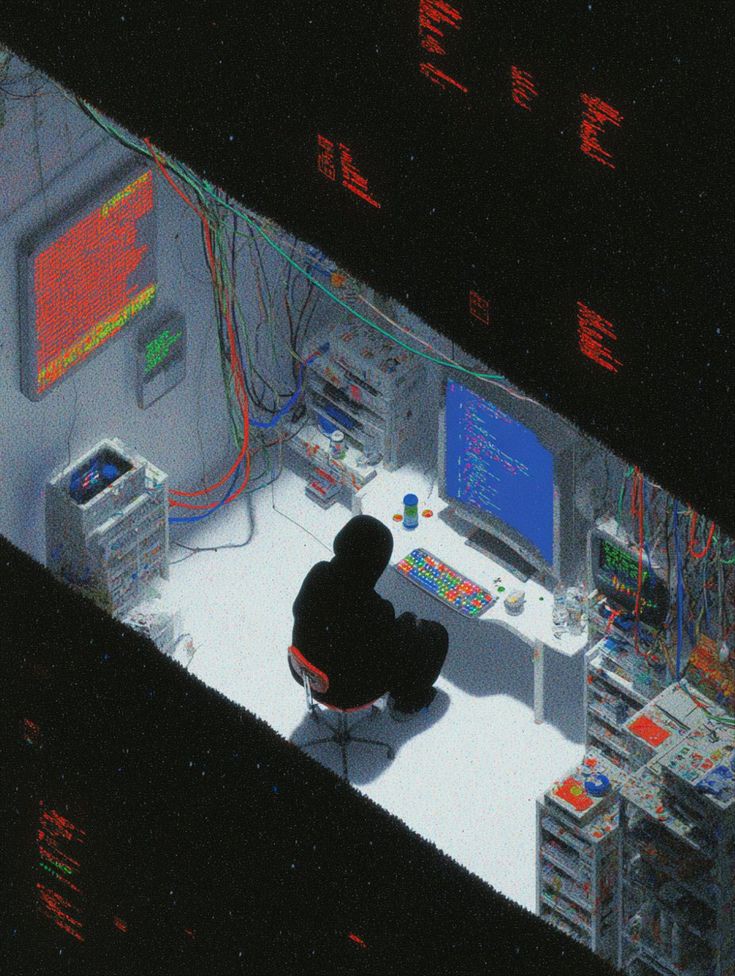

This is the maintenance underground: the people who operate the world's forgotten infrastructure, who speak dead programming languages fluently, who keep legacy systems alive long after their creators have moved on.

THE INNOVATION FALLACY

Tech culture operates on a simple narrative: new replaces old. Better disrupts worse. Progress marches forward. This story ignores what actually happens at scale.

SYSTEMS DON'T DIE—THEY ACCRUE

When a new technology emerges, it doesn't replace existing systems—it layers on top of them. The banking system still runs on COBOL. Air traffic control still uses FORTRAN. Government databases still rely on systems designed in the 1970s.

"Legacy code isn't legacy because it's old. It's legacy because it works and nobody understands it anymore."

The maintenance burden grows exponentially, but our attention remains fixed on the surface—the new apps, the latest frameworks, the disruptive startups.

THE COST OF FORGETTING

When knowledge about critical systems retires without being transferred, we create institutional amnesia. The system continues functioning, but only because a handful of people remember how it works. They become single points of failure in national infrastructure.

This is technical debt at civilizational scale.

UNSUNG ARCHETYPES: PROFILES FROM THE UNDERGROUND

THE ECONOMICS OF MAINTENANCE

Maintenance work follows different economic rules than innovation work:

THE CURSE OF INVISIBILITY

Good maintenance is invisible. Systems work, outages don't happen, updates proceed smoothly. This creates a perception problem: if nothing is breaking, what are we paying maintenance staff for?

The result: maintenance teams are first to face budget cuts during downturns, creating delayed-failure scenarios where systems collapse months or years later.

THE EXPERTISE PREMIUM

As knowledge about legacy systems becomes rarer, those who possess it gain disproportionate leverage. A COBOL programmer today can charge $300/hour—not because COBOL is valuable, but because COBOL knowledge connected to critical banking infrastructure is priceless.

This creates perverse incentives: the better you maintain a system, the more you ensure your own indispensability, but also guarantee the system will never be properly replaced.

THE TRANSFER PROBLEM

Maintenance knowledge resists documentation. It's contextual, experiential, and often learned through failure. You can't put "how to diagnose the weird memory leak that happens every third full moon" in a manual.

This knowledge transfers through apprenticeship, not documentation. But apprenticeships require time, trust, and organizational patience—resources that are disappearing.

SYSTEMIC VALUE: THE FOUNDATION OF INNOVATION

Maintenance provides three critical functions that innovation cannot:

INSTITUTIONAL MEMORY

Maintenance professionals carry the history of systems in their heads. They remember why certain decisions were made, what failures occurred, which workarounds became permanent. This memory enables continuity.

RISK CONTAINMENT

Every system accumulates entropy. Maintenance contains that entropy, preventing cascading failures. The maintenance underground manages the technical debt that enables innovation elsewhere.

STABILITY PROVISION

Innovation requires stable platforms. You can't build new applications if the database keeps crashing. Maintenance provides the stability that innovation consumes.

"The flashy startup changing the world runs on AWS. AWS runs on data centers. The data centers run on electrical grids. The grids run on control systems from the 1980s. Someone still knows how those work."

THE RISK OF INVISIBILITY: CASE STUDIES IN COLLAPSE

CASE 1: THE AIRLINE RESERVATION SYSTEM

Major airline's booking system fails for 48 hours. Investigation reveals: the last person who understood the transaction reconciliation process had retired six months earlier. His replacement had been hired from a "modern" background and never learned the legacy system. The failure cost $150 million in lost revenue.

CASE 2: THE HOSPITAL RECORDS LOCK

Regional hospital system loses access to 15 years of patient records. The encryption key management system depended on a single server running Windows NT 4.0. The administrator who maintained it had passed away unexpectedly. Recovery required hiring a consultant who specialized in "digital archaeology."

CASE 3: THE STOCK EXCHANGE GLITCH

Trading platform experiences millisecond-level timestamp errors that cascade into billions in erroneous trades. Root cause: the time synchronization system relied on hardware that hadn't been manufactured in 20 years. The maintenance team had been documenting warnings about component aging for five years. Management had classified it as "low priority technical debt."

RECOGNIZING THE MAINTENANCE LAYER

How to identify critical maintenance dependencies before they fail:

1. Map knowledge concentration: Where does critical knowledge exist in only one or two people?

2. Document the undocumented: What systems have no living documentation beyond oral tradition?

3. Identify single points of failure: Which individuals represent institutional memory about critical processes?

4. Track system age vs. support age: How old are your critical systems compared to the availability of people who understand them?

5. Measure bus factor: Literally—how many people would need to be hit by a bus before critical knowledge disappears?

THE PARADOX OF SUCCESS

The maintenance underground faces a fundamental paradox: their success makes them invisible, but their invisibility threatens their existence. The better they do their jobs, the less organizations value them—until they're gone.

This creates a system that's simultaneously robust and fragile. Robust because it continues functioning against all odds. Fragile because its continuity depends on unrecognized, undervalued labor.

The lights stay on because someone remembers which switches to flip. The question isn't whether those people exist—it's whether we'll notice them before they're gone.

SYSTEM NOTES

• Legacy systems aren't legacy because they're old—they're legacy because they work

• Maintenance knowledge resists digitization—it lives in people, not documents

• The most critical systems often have the least institutional knowledge about them

• Technical debt becomes civilizational debt when scaled across infrastructure

• Innovation consumes the stability that maintenance provides

• The maintenance underground operates on trust networks, not org charts

• System collapse often begins with knowledge retirement, not technical failure

Progress depends on what we choose to preserve as much as what we choose to invent.